Okay, here goes. I’m just going to say it.

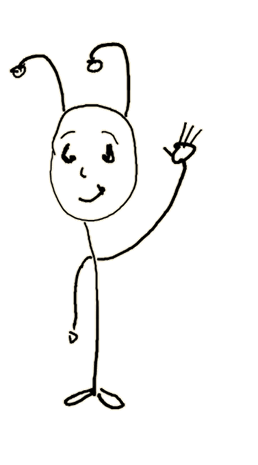

I’m an alien.

Like, from outer space.

My name is Wiptee-poof Blipticon. Greetings from Gliggablork!

I’m revealing myself because I want to explain the Fermi Paradox to you. I can no longer stand by while you people spout nonsense and freak out over nothing. The answer will put you at ease.

Your cosmologists and theoretical physicists are baffled by a number of unresolved mysteries, e.g. dark energy, dark matter, baryonic asymmetry, quantum gravity, the blackhole information paradox, the Vacuum Catastrophe, the Problem of Time, and the Fermi Paradox, just to name a few.

Many of these are tied together such that the answer to one automatically resolves another. The Fermi Paradox and dark matter are like that.

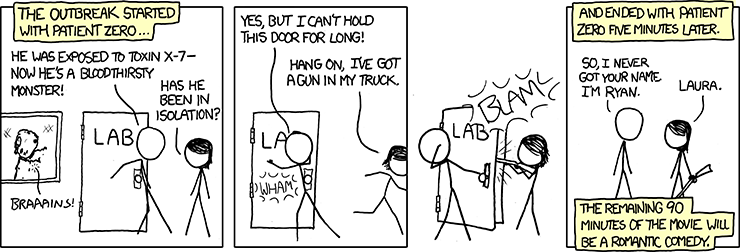

One day in the summer of 1950, the physicist Enrico Fermi had an epiphany. He realized that there’s a high probability that intelligent aliens exist, yet there’s a lack of evidence that they actually do, which is weird. When the epiphany hit him, he famously blurted to his research buddies at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, “But where is everybody?”

The answer:

We’re everywhere.

Your scientists have correctly theorized the following:

- With 70 sextillion stars in the universe, and with planets orbiting most of them, life should be abundant.

- Even if intelligent lifeforms only evolve on a small percentage of these planets, there should be multiple alien civilizations out there.

- Some of these civilizations must have started millions of years ago. By now they must be super advanced.

- And they’ve had time to spread everywhere.

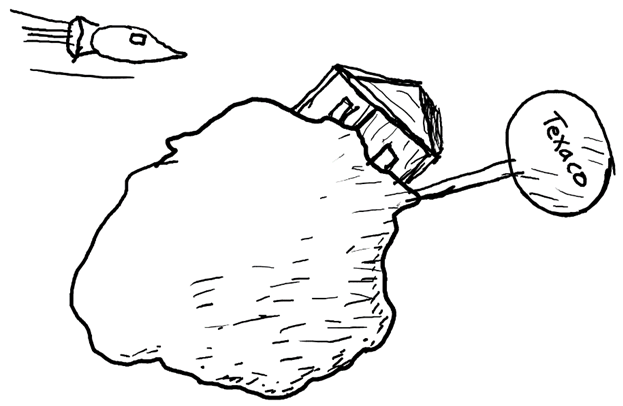

If these statements are true, why don’t Earthlings see evidence for aliens, like derelict probes or gas stations on asteroids?

To explain the answer, I first need to clarify a couple of misconceptions that show up in your science fiction.

Firstly, there are (almost) no evil alien civilizations. If you think about this rationally for a minute, it’s clear why.

As you’ve guessed, life is prolific in the universe. And not all of it is very nice. There are indeed mean little beasties out there amongst the stars. Actually, there’s an unthinkably large number of them.

But it turns out that there’s an evolutionary pattern that is so reliable, we consider it a law:

Technological advancement requires cooperation.

When you contemplate your own species, what may come to your mind is the selfishness and violence. You project this onto alien species.

But we’re not like that. And you guys aren’t nearly as bad as you think, either, and you’re getting better quickly.

As your technology advances, the level of cooperation required to continue advancing grows, and the utility in conflict decreases. Selfishness reaps rewards in the short term, but it doesn’t pay off in the final measure. This holds true even in regard to the worst sort of technological advancement: weapons of mass destruction.

When you consider, for example, a missile with a nuclear warhead, you might look on it with disgust and think, “We are such warlike creatures.” But consider the supply chain required to produce that missile – the networks of people and corporations and countries that must work together to make such a thing possible. The fancier the missile, the more cooperation and interdependence is involved in producing it. This interdependence diminishes the incentives for war. If the missile is used to destroy any part of the great web of cooperation that produced it, then no more missiles can be made.

Anything imaginable is possible when you work together. But when you stop working together, advancement stops. It doesn’t only stop; it backslides. The supply chains break. The institutions that perpetuate knowledge are destroyed. Civilization wanes.

This is the Great Filter:

Evil is inherently self-destructive.

Evil species can’t advance beyond a certain point because their inability to cooperate is naturally self-limiting.

And so, the most technologically advanced alien civilizations, by this law, are also highly, intensely, passionately, religiously cooperative. I can’t overstate how much value we put on getting along with others.

Now, I admit, once every blue moon, by some perverse miracle, an advanced alien civilization that is evil does emerge.

But they’re vanishingly rare. And they don’t get very far. They’re massively outnumbered by the good guys, like my people, the Gliggablorks, and they’re much less advanced than us. So, we deal them. Non-violently.

The second misconception most Earthlings hold is that the pace of technological advancement is always linear.

Technological advancement accelerates, and it brings social advancement with it.

The reason you assume it’s linear is because roughly linear advancement is what you’ve experienced historically. But your civilization is young.

Once a civilization creates truly useful AI, as your civilization is on the brink of doing, the pace of technological advancement accelerates exponentially or even logarithmically. It explodes.

This is because AI improves the efficiency in anything people do. And one thing people do is create and improve AI systems. Successive generations of AI therefore improve faster and faster.

Every alien civilization jumps virtually overnight from Type 0, where you’re currently at, to Type III on the Kardashev scale.

That’s why most of your science fiction is so silly. You dwell on stages of technological development that no alien civilization has actually experienced – because we skip them.

There are no intermediary levels of advancement. The starships and spacesuits and laser battles that you guys like to imagine are completely off base. Star Wars? There are no wars in space! At least not ones that span more than a single solar system.

None.

What is actually happening out there amongst the stars is way, way cooler than that.

That brings us to the effect we call Unification.

However unique the biology of any given alien species may be, however different they may be linguistically, socially, and culturally from all other aliens, when they merge with their computers and then experience explosive growth in their intelligence and technology, they change into something else. Their biological components take on a reduced role. As the organizing principle of their lives moves away from the mere fulfillment of biological imperatives, they ascend to a state that is essentially similar to all the other advanced alien civilizations.

They unify.

This is a process that is repeating in every galaxy across the universe. Unification is similar to convergent evolution in the field of biology. And it works like a biological law, like evolution itself.

Did you know six new stars are born in the Milky Way each year?

Unification is so reliable that you can make predictions about it in the same way you can predict star births, supernovas, black holes, pulsars, quasars, and everything else that is going on up there in the night sky.

A new species will unify once every 100 Earth years. That’s when their star disappears from sight.

Now to answer the Fermi Paradox:

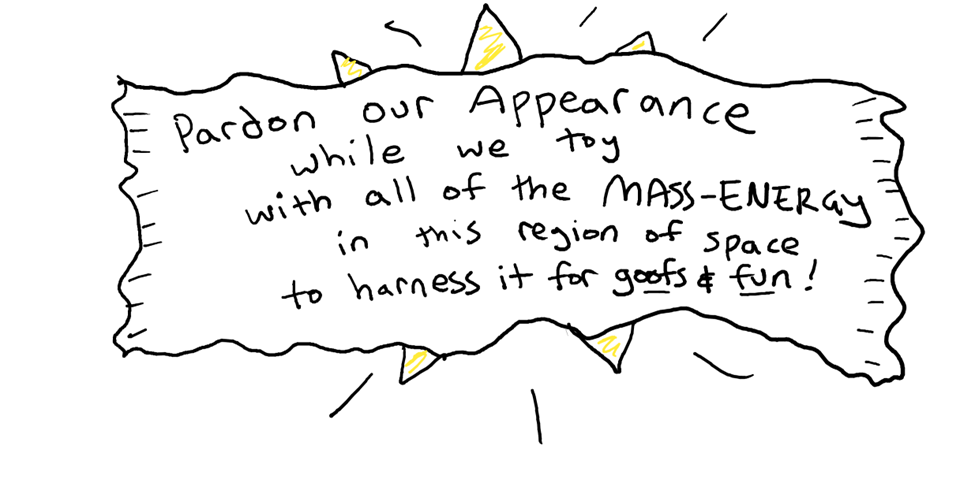

The reason so much of the galaxy is dark to you is because we’re using it for energy. The way we generate energy is more complicated (and efficient) than a Dyson Sphere, but like a Dyson Sphere, our process hides matter and light but not gravity.

The 27% of the universe that you cannot see, but that you’ve correctly deduced from its gravitational effects must exist, is us.

The reason you don’t see our probes is because we don’t often need probes, and when we do, we’re not amateurs. We don’t use tech you would see.

The reason we aren’t up in your grill is because we’re giving you space to figure yourselves out.

UFOs aren’t us. Sorry, but the idea that an alien spaceship would be advanced enough to travel thousands of light years across the galaxy only to hit a goose in your upper atmosphere and crash in New Mexico is phenomenally stupid. And so is the idea that we’re abducting humans to sodomize you with metallic space dildos.

We don’t need to do any of that stuff to learn about you.

We can study you from the comfort of our homes. You can’t even begin to imagine how awesome our telescopes are.

And we’re not after the natural resources on your planet, either, like your water or your pickle juice or whatever. It’s not that Earth isn’t beautiful and special. But the minerals and other elements on Earth are abundant throughout the universe. We have all the pickle juice we need, and we don’t have to enslave or eradicate living beings to get more.

The only interesting thing to us on Earth is you.

(And not because we want to eat you. That’s gross.)

When you do see us, it will be because we want you to see us. And that hasn’t happened yet. When it does, it’ll be public and you’ll definitely know.

So that’s the answer to the Fermi Paradox!

I hope you’ve enjoyed it. 🙂

I’m four chapters in. And I just couldn’t wait to post about it. My early review (no spoilers):

I’m four chapters in. And I just couldn’t wait to post about it. My early review (no spoilers):